Education in times of COVID-19: How does stress affect learning?

In most societies, people typically greet each other by showing interest in the other person’s well-being. In English, for example, it is quite common to ask, “How are you?” Similar expressions are found in almost all languages. How people feel—that is, their emotional state—correlates with their mood and is crucial for all human relationships, as well as for learning.

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly altered educational dynamics in most schools around the world. It has also become a stress test for educational systems and policies, as well as for students and teachers, affecting their emotional states. The academic consequences of these changes may vary significantly depending on the responses made by educational administrations as well as the income of each family, the most affected being those from low and lower-middle incomes1. According to the Policy Brief entitled “Education under COVID-19 and beyond” published in August 2020 by the United Nations1, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected nearly 1.6 billion learners in every corner of the world. Closures of schools and other learning spaces have impacted 94% of the world’s student population, and up to 99% in low and lower-middle income countries. According to this UN brief1, learning losses threaten to extend beyond this generation and erase decades of progress, not least in girls’ educational access and retention, exacerbating preexisting educational, economic, and social disparities.

The closure of educational institutions may also hamper the provision of essential services to children, including nutritious meals, affect the ability of many parents to work, and increase the risks of intrafamilial violence, mostly against women and girls. Such consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic imply a major threat not only to children, adolescents, and young adults, but also to what is thought to be the essence of education: “Education is not only a fundamental human right. It is an enabling right with direct impact on the realization of all other human rights. It is a global common good and a primary driver of progress across all 17 Sustainable Development Goals2,3 as a bedrock of just, equal, inclusive peaceful societies. When education systems collapse, peace, prosperous and productive societies cannot be sustained”1.

Emotionality

Actions taken by most governments to manage the COVID-19 pandemic, such as quarantines, home confinement, and online education, may affect students’ emotional stability, which is closely correlated with efficient learning, coping, and well-being4. A simple questionnaire, originally developed for adolescents, can help to reveal an individual’s emotional state5, and may be useful in many situations to understand how they feel:

- When I’m in a bad mood, I can think of something happy.

- Criticism from others will make me sad for a long time.

- No matter what difficulties I meet, I can stay in a good mood.

- My mood is not easily disturbed by the outside world.

- Unhappy things will make me upset for a long time.

- I can adjust my negative emotions quickly.

- Unpleasant events during the day often keep me awake at night.

- In the face of stress or frustration, I can find my own comfort.

- No matter how bad I feel, I can always look on the bright side.

- I feel bad when people misunderstand me.

- It is hard for me to calm down after an argument.

Several works have shown that quarantine and home confinement may affect emotionality by increasing isolation and lonely feelings, stress, and anxiety6-8.

Effects of isolation on brain morphology, biochemistry, and learning

Various studies have shown that between 16% and 25% of people have experienced feelings of extreme isolation during COVID-19 quarantines6,7. These feelings also affect children and adolescents due to prolonged physical isolation from their peers, teachers, extended families, and community networks. Although social isolation is not necessarily synonymous with loneliness, more than one third of adolescents in some countries have reported high levels of loneliness9 and almost half of 18- to 24-year-olds reported feeling lonely during COVID lockdowns10.

Several changes in brain function that occur during prolonged isolation may affect basic learning skills. In a study conducted on an Antarctic expedition in which nine people lived in isolation for 14 months11, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) brain scans revealed a size reduction in several hippocampal areas which may affect the formation and consolidation of long-term memory, as well as a decrease in grey matter in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the left orbitofrontal cortex, which may affect working memory, decision-making processes, sensory integration, affective value of reinforcers, expectation, and the regulation of emotion. At a molecular level, a reduction in Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) serum concentrations was also detected11. Considering that that BDNF encourages the formation of new synapses and neurons, and that new synapses are needed for the acquisition and consolidation of new knowledge, this reduction may affect learning and behaviour. Interestingly, BDNF levels had not returned to normal one and a half months after isolation ended.

While the above study was not conducted in the context of COVID-19 quarantines, its findings allow us to hypothesize on the effects of prolonged feelings of isolation, although the differences between the severe conditions of the Antarctic expedition and the current situation are profound.

Stress

Another reported effect of the COVID-19 outbreak and quarantine is increased stress and anxiety12, which may affect up to 70% of students8. Stress is a state of mental or emotional strain resulting from adverse or demanding circumstances13,14. The main causes of stress and anxiety among students during the COVID-19 pandemic are social isolation and loneliness, which we have just addressed, as well as uncertainties about teaching (traditional classroom setting versus online), holiday periods and e-exams, lack of technical support, and other effects on family dynamics. However, not all students experience the same levels of stress and anxiety. The extent may depend on prior psychological vulnerability, specific environmental conditions, general beliefs about the pandemic, and the effectiveness of online education, domestic coexistence, living conditions, access to the internet and digital technology, and other preexisting social, cultural, and economic conditions15,16.

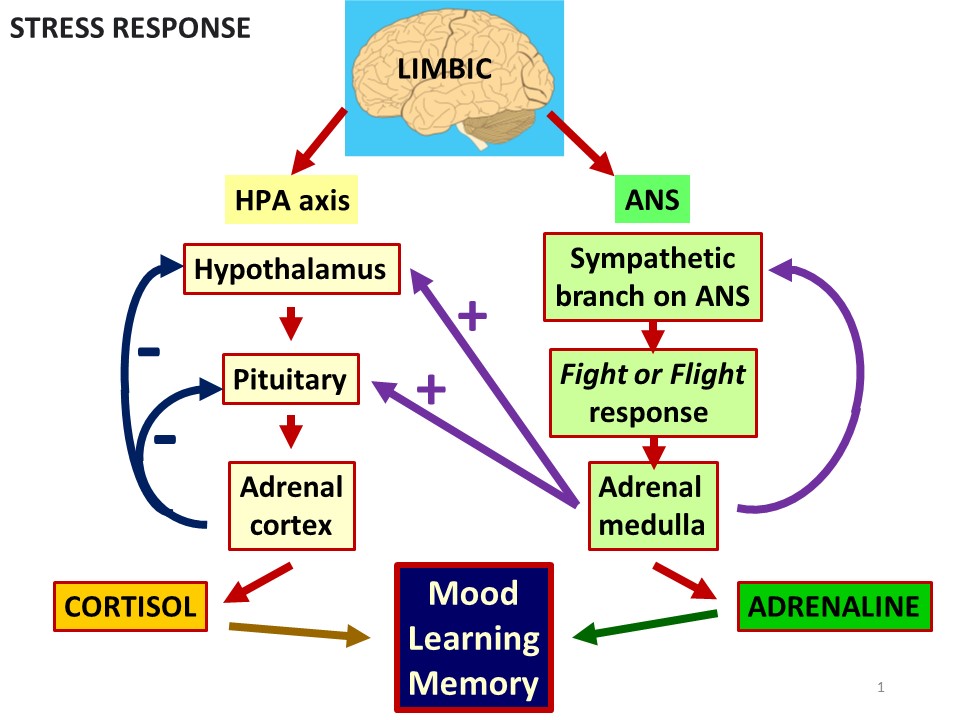

The stress response is very complex, with numerous mediators involved. Briefly, two major stress systems appear to be critical for the modulation of learning and memory processes. These are the rapid autonomic nervous system and the slower hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis17 (see Figure 1). Within seconds of a stressful stimulus, the autonomic nervous system is activated, leading to the release of catecholamine neurotransmitters such as noradrenaline, from both the adrenal medulla and the locus coeruleus in the brain. Catecholamines prepare the body for “fight-or-flight” responses and rapidly affect neural functioning in several brain regions critical for learning and memory, such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex. A second system is also activated in response to stress, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, about 10 seconds later than the autonomic nervous system, resulting in the release of corticosteroids such as cortisol from the adrenal cortex. Cortisol can enhance or impair memory function, depending largely on how much time passed between the stressful event and the memory process. In this regard, it is known that moderate release of corticosteroids may enhance memory consolidation when close to the time of the event, but conversely they may impair memory consolidation if they are released a while before or after the event. Interestingly, another group of corticosteroids known as glucocorticoids may induce atrophy of the hippocampus, especially when chronic stress conditions turn acute, impairing long-term memory storage. Moreover, the physiological impact of repeated or prolonged chronic stress, called allostatic load, may cause exhaustion and breakdown18.

Figure 1. Diagram of the two major stress systems

Effects of stress

Several studies of the likely effects of stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in different populations all over the worlde.g.,5,12,15,16,19-34 have shown that, in the absence of support from family, friends, and other individuals, toxic stress and moderate stress may cause an increase in the following:

- Anxiety—i.e., a feeling of worry, nervousness, or unease about something with an uncertain outcome, which seems to be more pronounced in women than in men.

- Depression—i.e., feelings of sadness or a loss of interest in activities that were once enjoyed. Symptoms can vary from mild to severe and can include feeling sad or having a depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed, changes in appetite, trouble sleeping or sleeping too much, loss of energy or increased fatigue, increase in purposeless physical activity (e.g., inability to sit still, pacing, handwringing), feeling worthless or guilty, difficulty thinking, concentrating or making decisions, and thoughts of death or suicide.

- Anger—i.e., a strong feeling of annoyance, displeasure, or hostility that may cause aggressive behaviours and violence.

- Consumption of drugs (e.g., alcohol, marijuana) and other distressing or activating substances (e.g., caffeine, energy drinks, sugary food) by adolescents and young adults.

In parallel, stress may also cause a decrease in the following:

- Emotional regulation—i.e., the ability of an individual to modulate an emotion or set of emotions, which has been correlated with an increase in anger and fear, and a decrease in intentional deployment, cognitive reevaluation, and response modulation.

- Emotional resilience—i.e., the ability to adapt to stressful situations and cope with life’s ups and downs, which has been correlated with a decrease in learning management skills and coping ability.

- Psychological well-being—i.e., the inter- and intra-individual levels of positive functioning that can include one’s relatedness to others and self-referent attitudes, including one’s sense of mastery and personal growth, which has been correlated with an increase in academic failure.

- Self-efficacy—i.e., a person’s belief in their capability to exercise control over their own functioning and over events that affect their life, which has been correlated with an increase in academic failure.

What about teachers and educators?

Teachers and educators may be affected in the same way, so teacher training in coping with stress and preventing burnout, and in improving technological competence, emotional regulation, and resilience is needed35,36, not only for their own benefit but also for that of their students.

Conclusions

All of these related processes that can be triggered by measures taken in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as quarantine, home confinement, and online education, influence the cognitive processes involved in learning, from motivation to the processing of information, the establishment of significant links between new content and previous knowledge, and the use of what has been learned in tests and exams. In other words, these measures affect emotionality. To cope with this situation, efforts must be directed towards decreasing students’ stress and anxiety and reducing their feelings of loneliness and isolation. So, the casual question “How are you?” acquires even more importance than usual.

References

- United Nations. (2020). Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (Accessed December 19, 2020).

- UNESCO. (2015). Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656. (Accessed December 19, 2020).

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., Darling-Hammond, L., & Krone, C. R. (2019). Nurturing nature: How brain development is inherently social and emotional, and what this means for education. Educ. Psychol. 54(3): 185-204.

- Zhang, Q., Zhou, L., & Xia, J. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on emotional resilience and learning management of middle school students. Med. Sci. Monit. 26: e924994.

- Smith, B. & Lim, M. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Heal. Res. Pr. 30, 3022008

- Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395(10227): 912-920.

- Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 22(9): e21279.

- Oxford ARC Study. (2020). Achieving resilience during COVID-19 weekly report 2. Available at: http://mentalhealthresearchmatters.org.uk/achieving-resilience-during-covid-19-psycho-social-risk-protective-factors-amidst-a-pandemic-in-adolescents/. (Accessed December 23, 2020).

- Mental Health Foundation. (2020). Loneliness during Coronavirus. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/coronavirus/loneliness-during-coronavirus. (Accessed December 23, 2020).

- Stahn, A. C., Gunga, H. C., Kohlberg, E., Gallinat, J., Dinges, D. F., & Kühn, S. (2019). Brain changes in response to long Antarctic expeditions. N. Engl. J. Med. 381(23): 2273-2275.

- Singh S., Roy M. D., Sinha C. P. T. M. K., Parveen C. P. T. M. S., Sharma C. P. T. G., & Joshi C. P. T. G. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 20:113429.

- McEwan, B. S. (2016). In pursuit of resilience: Stress, epigenetics, and brain plasticity. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1373: 56–64.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Judge, L., & Rahman, F. (2020). Lockdown Living: Housing Quality Across the Generations. Westminster: Resolution Foundation, Corp Creator.

- Majumdar, P., Biswas, A., & Sahu, S. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: Cause of sleep disruption, depression, somatic pain, and increased screen exposure of office workers and students of India. Chronobiol. Int. 20 1–10.

- Banich, M.T., & Compton, R.J. (2018). Cognitive Neuroscience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ogden, J. (2004). Health Psychology: A Textbook (3rd ed.). Open University Press – McGraw-Hill Education.

- Fernández Cruz, M., Álvarez Rodríguez, J., Ávalos Ruiz, I., Cuevas López, M., de Barros Camargo, C., Díaz Rosas, F., González Castellón, E., González González, D., Hernández Fernández, A., Ibáñez Cubillas, P., & Lizarte Simón, E. J. (2020). Evaluation of the emotional and cognitive regulation of young people in a lockdown situation due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11: 565503.

- Fernández C. M. (2015). Formación y Desarrollo de Profesionales de la Educación: Un Enfoque Profundo. Blue Mounds, WI: Deep University Press.

- Gross J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospect. Psychol. Inq. 26: 1–26.

- McRae K. (2016). Cognitive emotion regulation: A review of theory and scientific findings. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 10: 119–124.

- Stikkelbroek Y., Bodden D. H., Kleinjan M., Reijnders M., & van Baar A. L. (2016). Adolescent depression and negative life events, the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation. PLoS One 11:1062.

- Wang, C., & Zhao, H. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety in chinese University students. Front. Psychol. 11:1 168.

- Alemany-Arrebola, I., Rojas-Ruiz, G., Granda-Vera, J., & Mingorance-Estrada, Á. C. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 on the perception of academic self-efficacy, state anxiety, and trait anxiety in college students. Front. Psychol. 11: 570017.

- Huarcaya-Victoria J. (2020). Mental health considerations about the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Pública 37: 327–334.

- Asmundson, G.J., Taylor, S. (2020). Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV Outbreak. J. Anxiety Disord. 70: 102–196.

- Ozamiz N., Dosil M., Picaza N., & Idoiaga N. (2020). Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cad. Saúde Públ. 36: e00054020.

- Shigemura, J., Ursano, R.J., Morganstein, J.C., Kurosawa, M., & Benedek D.M. (2020). Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psych. Clin. Neurosci. 74: 281–282.

- Torales J., O’Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J. M., Ventriglio A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psych. 66(4): 317–320.

- Valiente C., Vázquez C., Peinado V., Contreras A., Trucharte A. (2020). Estudio nacional representativo de las respuestas de los ciudadanos de España ante la crisis del COVID-19: respuestas psicológicas. Available online at: https://n9.cl/pi7n. Accessed November 29, 2020.

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 17: 17–29.

- Elsalem, L., Al-Azzam, N., Jum’ah, A.A., Obeidat, N., Sindiani, A.M., Kheirallah, K.A. (2020). Stress and behavioral changes with remote E-exams during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study among undergraduates of medical sciences. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond). 60: 271-279.

- Sundarasen, S., Chinna, K., Kamaludin, K., Nurunnabi, M., Baloch, G.M., Khoshaim, H.B., Hossain, S.F.A., Sukayt, A. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 and lockdown among University students in Malaysia: Implications and policy recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17(17): 6206.

- Pozo-Rico, T., Gilar-Corbí, R., Izquierdo, A., Castejón, J.L. (2020). Teacher training can make a difference: Tools to overcome the impact of COVID-19 on primary schools. An experimental study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17(22): 8633.

- Klapproth, F., Federkeil, L., Heinschke, F., Jungmann, T. (2020). Teachers’ experiences of stress and their coping strategies during COVID-19 induced distance teaching. J. Pedagog. Res. Advanced online publication.